A Constitution of Unity

The fifth and final of Levin’s Constitutional frameworks.

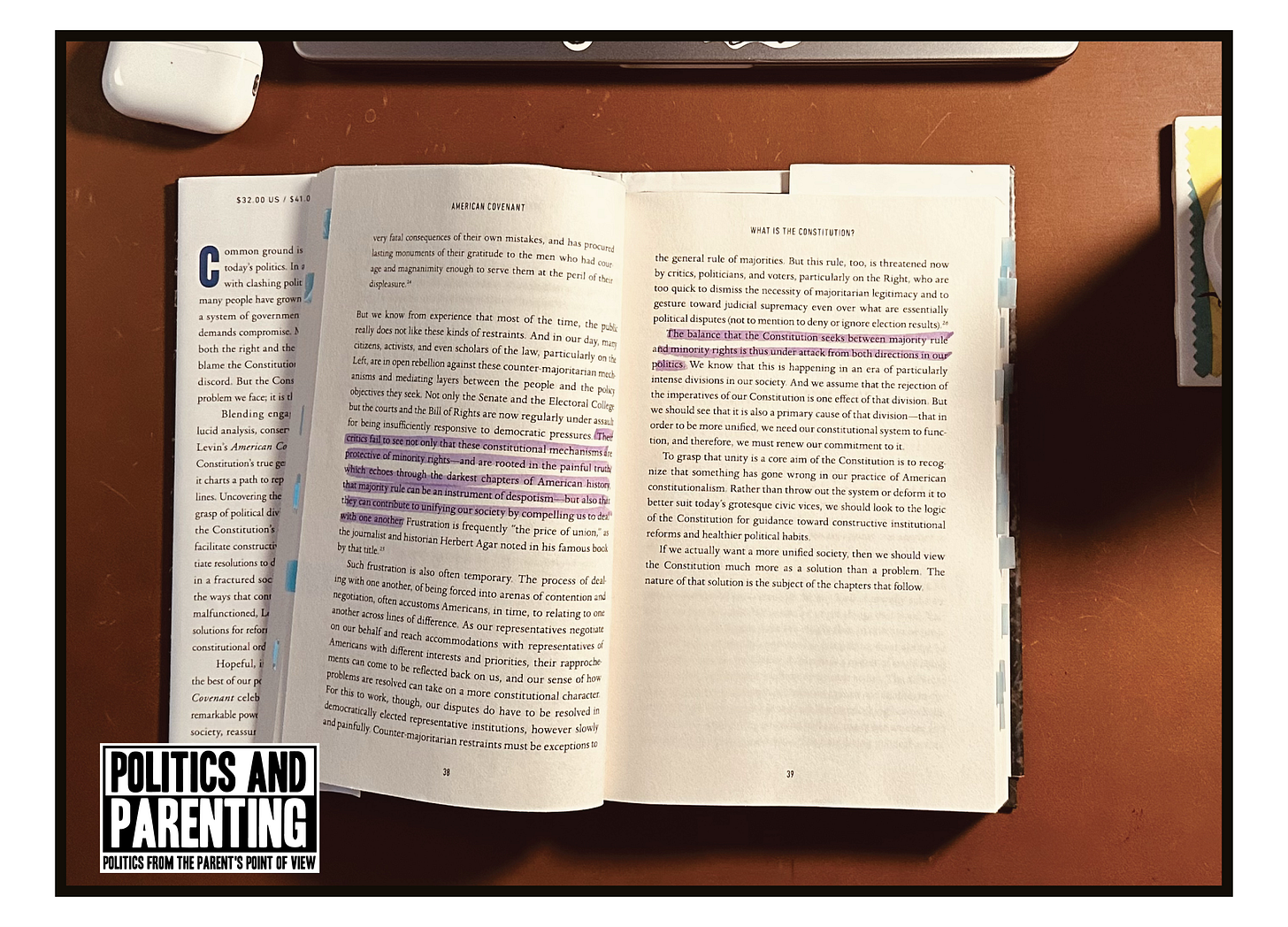

The fifth and final of Levin’s Constitutional frameworks is unity. (If you missed the first four, check them out here: legal, policymaking, institutional, political.) Unity is the primary object of the Constitution. The ambition is right there in the preamble: “We the People of the United States, in Order to form a more perfect Union.” It assumes unity while acknowledging the challenges.

America’s first Constitution was the Articles of Confederation. It structured the government through the Revolutionary War and the following five years. However, the Union was deeply divided; “the first twenty-three of the eighty-five Federalist Papers” were devoted to preserving the Union. The call for a new Constitution was made because the Articles were failing to keep America united.

“The very idea of a written Constitution that stands apart from regular legislation as the framework of a regime is rooted in the ambition to establish some such common ground in a permanently factious polity. By drawing a distinction between views about the system of government and views about policy and interests, it stakes out space for agreement that can allow our disagreements to be dealt with more constructively.”

The Constitution creates a space for the different factions of our society to debate and resolve differences. Levin stresses the importance of disagreeing constructively within that space.

“The breakdown of political culture in our day is not a function of our having forgotten how to agree with one another but of our having forgotten how to disagree constructively. And this is what our Constitution can better enable us to do. As a framework for unity, the Constitution functions as a means of rendering disagreement more constructive.

It does this, above all, by rendering disputing factions in our politics into parties to a substantive debate about how to proceed together. In an essentially democratic system of government, this may be achieved by multiplying the number of factions in society (so that there is not a permanent majority faction) and by restraining the power of majorities (so that a narrow majority is not enough to win every argument). Our Constitution multiplies the number of factions in a variety of ways–– beginning (as Madison famously noted) with the sheer size of our republic but also extending to the profusion of modes of election and appointment to various offices and the variety of power centers and competing wielders of authority operating simultaneously. And it restricts the power of majorities through an assortment of mediating mechanisms that require agents of change to engage in a complicated dance of coalition building.”

By multiplying the number of factions, it makes it difficult for one faction to grow large enough and control the rest. In a free society, that is, a society that multiplies factions instead of limiting them, when a faction grows too large, it divides. This happens because there will always be different opinions inside a faction; the more opinions, the more friction. The freedom created by multiplying factions limits the friction. Our republic unites us by recognizing our right to disagree and creates a space for us to disagree constructively. We make change by building relationships with competing factions and carving out a middle ground.

Levin warns that the system's checks and balances and the “mediating layers between the people and the policy objectives they seek” are under assault. Undermining the mediating layers consolidates factions and limits debate.

“Their critics fail to see not only that these constitutional mechanisms are protective of minority rights–– and are rooted in the painful truth, which echoes through the darkest chapters of American history, that majority rule can be an instrument of despotism–– but also that they can contribute to unifying our society by compelling us to deal with one another.”

We may not agree with the majority, but we must acknowledge their responsibility to govern. We may not agree with the minority, but we must not ignore their rights to exist. The Constitution carves out a space for these two groups to co-exist. However, they are in a constant battle to defeat each other. It’s clear something has gone wrong, and Levin proposes that the renewal of the Constitution and a better understanding of its framework can guide and unite us.

“To grasp that unity is a core aim of the Constitution is to recognize that something has gone wrong in our practice of American constitutionalism. Rather than throw out the system or deform it to better suit today’s grotesque civic vices, we should look to the logic of the Constitution for guidance toward constructive institutional reforms and healthier political habits.”

We each live in our own bubble. It can be called a faction or a group. We only see what’s in front of us. We can read about other factions and visit them, but we may not fully understand them unless we decide to join them.

Each person belongs to multiple factions centered around common interests like a baseball team, chess club, or rock band. In my life, I have belonged to many factions around a common interest, such as fantasy and flag football, whiskey, and poker. Inside each faction was a diverse group of individuals who belonged to other factions. Some of them hunted, some were musicians, some were ex-military. While I would never understand their unique experiences unless I decided to become a hunter, musician, or join the armed forces, which are unlikely at this point in my life, I learned about them.

Learning about them broadened my worldview and allowed me to see a bigger picture. I built relationships that changed my life and helped me grow. Each faction formed me in a way. The way our constitution is designed to form healthy political habits. It creates a space to unite our factions around common interests and learn about our differences. To solve our political dysfunction, we must, as Levin says, “view the Constitution much more as a solution than a problem.”

The assault on the Constitution comes from both sides of the aisle, Republicans and Democrats, MAGA and Progressives; as citizens, we must not bow to those trying to control the system. Instead, we must educate ourselves on how the Constitution protects us from oppression, tyranny, and anarchy.

That concludes Chapter One of American Covenant: What is the Constitution? I hope you enjoyed reading about Levin’s Five Constitutional Frameworks: legal, policymaking, institutional, political, and unity. He explained how the constitution is a set of rules and guidelines that divide power and share responsibility; it empowers people to write policy and creates institutions to carry out the work of governing while providing a political structure that balances the rule of the majority with the rights of the minority all while uniting the different factions of our diverse union. In upcoming posts, I will highlight some of Levin’s insights from Chapter Two: Modes of Resolution. Be sure to subscribe so you don’t miss out!

Peace & Love,

Jeff Mayhugh