Radical ideas are surfacing from both the left and right: Kamala Harris supports “some form of reparations,” Tim Walz says, “the Electoral College needs to go,” and Donald Trump advocates invoking the Alien Enemies Act to round up undocumented immigrants. These ideas may seem unrelated, but they all share a critical constitutional foundation: representation through apportionment.

While political leaders push these radical ideas for popularity, the root problem remains: Americans are underrepresented. Power is concentrated in fewer hands, corruption spreads, and Congress continues to abdicate its authority. The real crisis isn't new agendas—it’s a broken system of representation.

Citizens don’t feel they have a say in what happens. The debt grows, the border is overrun, and power is pushed further and further away from average citizens. It’s a game of who you know and how much you can fundraise, and far too many Americans don’t know the right people or have time or money to compete for their attention. Representation is out of reach for a majority of Americans.

Freedom in our republic rests on representation—the power to have a say in the rules that govern us. Our voice in government is held in the democratically elected House of Representatives. But since 1929, that freedom has been limited as representation has been diluted. Gerrymandering serves party success over democracy, and executive authority grows unchecked as power slips away from Congress.

Today in The Hill, I discuss how population shifts from California to Texas could shock the nation and deepen divisions. If Texas goes blue, Trump may repeat his 2020 playbook—refusing to concede, launching legal challenges, pressuring state officials, and encouraging public disobedience. Some members of Congress might even object to certifying the election, and Trump could appeal to the Supreme Court.

Navigating this political turmoil requires understanding basic constitutional principles. At the heart of today’s challenges is the apportionment (or lack thereof) of representation in the House of Representatives. Article I, Section 2 of the Constitution requires a census every ten years to adjust the number of House seats based on population changes. Like the one we are seeing in Texas. Until 1911, the House expanded alongside population growth.

During the Constitutional Convention, representation was the most contentious issue, leading to the bicameral Congress and the Three-Fifths Compromise. The 14th Amendment expanded representation to former slaves, but immigration and urbanization in the Gilded Age revived apportionment debates. In 1920, urban populations surpassed rural populations for the first time, but Congress resisted change, fearing the rise of urban political power.

In 1921, the dramatic population shifts led to a heated debate about apportionment. Many members of the House already felt it was too large and were against increasing the number in 1890, 1900, and 1910. Some didn’t believe the 1920 census was accurate due to many American men serving in WWI. So, for the first time in history, Congress failed to fulfill its constitutionally delegated responsibility. The first bill was strangled in committee, and the Senate filibuster killed the second.

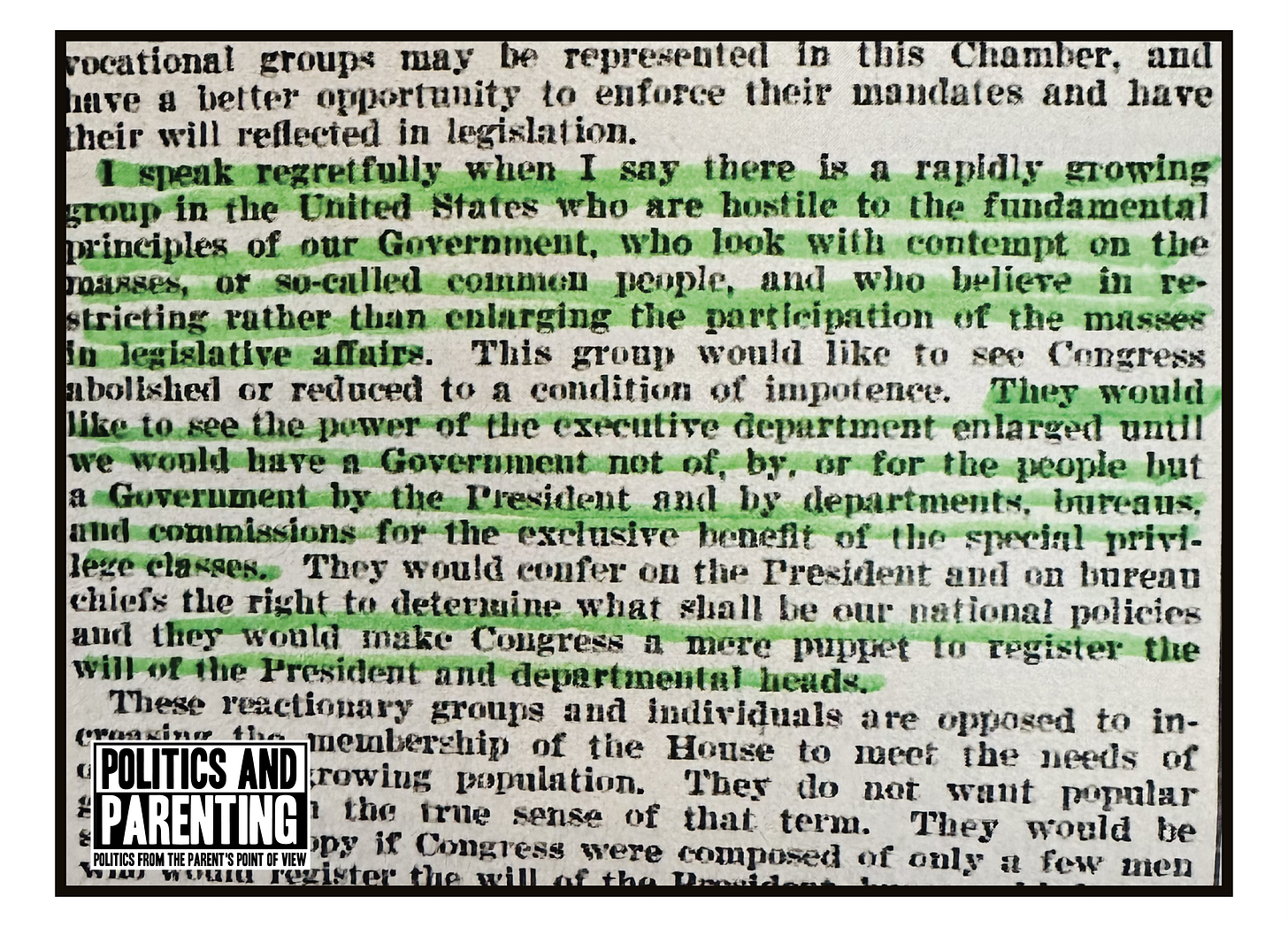

Reading through the apportionment debates of 1928 and 1929 is fascinating. They sound much like today's problems: a failure of Congress to act, a delegation of authority to a bureaucratic agency, a futile debate about “unnaturalized aliens” critiques of the “metropolitan press,” and polarization between the growing urban areas and rural America.

The debate on all sides of the issue was filled with passion. Members were prepared; there are references to George Washington at the Continental Convention and quotes from James Madison and Daniel Webster. Crucial questions emerged: Should representation be based on citizens only or all residents—including non-citizens? How many Representatives are too many? Why 435? How can the representation between large and small states and urban and rural areas be balanced? Should the power remain in Congress?

The debate ended in 1929. Congress passed the Permanent Apportionment Act of 1929, capping the House at 435 seats, delegating constitutional authority to a bureaucratic agency, and counting all persons for apportionment, including undocumented immigrants. This decision, motivated by skepticism of census results and fears of urban political dominance, would forever alter the balance of representation.

Since the House was capped, the U.S. population has grown from 100 million to over 330 million, and the citizen-to-representative ratio has ballooned from 1:220,000 to 1:750,000. Members of Congress are overwhelmed; they continue to delegate their authority to bureaucracies, leaving citizens unrepresented. The cap also creates disparities in the Electoral College, encourages gerrymandering, and disenfranchises urban communities, including many Black Americans.

The 14th Amendment sought to ensure equal representation for formerly enslaved people by counting them fully in the apportionment process. However, the 1929 cap disproportionately harmed Black Americans in growing urban centers like Atlanta and Detroit. Without additional representatives, Black voters faced diluted political power in overcrowded districts. If Harris truly seeks to address the legacy of slavery, Jim Crow, and segregation, expanding representation should be the first step.

Because the House seats are fixed at 435, gerrymandering congressional districts in key states affects how electoral votes are awarded. Instead of eliminating the Electoral College, as Walz suggests, expanding the House would make it more reflective of the popular vote and lessen the power of state legislatures to manipulate the electoral vote. As Jonah Goldberg recently argued, it "would alleviate much of the ‘undemocratic’ nature of the Electoral College.”

Rather than invoking executive overreach to deport immigrants, as Trump proposes, Congress could enact a new apportionment bill that counts only legal citizens for representation. This approach would encourage Congress to develop clear immigration rules and ensure that political power reflects the will of citizens.

No matter who wins the election in November, citizens must speak up for their representation to quell the radical populists. The capped house infringes on a citizen’s right of representation. Expanding the House of Representatives secures democracy, expands freedom, balances power, and increases accountability. It’s the first step in reforming a radically broken political system that supports radical political figures for President.