Threads of the Old Republic

What led to the New Democratic power?

The anxiety of the American people during the winter of 1814-15 was reaching a level not seen since the days of Valley Forge. The War of 1812 was taking a toll on the fragile Union. The White House was burned in August, and now there was a group of Federalists plotting against the administration and maybe the Union. Meanwhile, a powerful British armada and land forces were planning to move through the American South and slice the young nation in half. In New Orleans, Andrew Jackson led a patchwork of militia from Tennessee, New Orleans, and black volunteers from Haiti to defend the important city from Wellington’s professional British army. Across the stormy Atlantic, there was no news from Ghent about the treaty negotiations other than the British wanted to humiliate and divide the young American nation that most Britons never took seriously. Prospects were bleak, and the American experiment of self-governance looked to be coming to an end.

And then, news from New Orleans. Andrew Jackson and his ragtag fighting force defeated Wellington’s forces, securing the South, West, and the Republic. As H.W. Brands puts it in his comprehensive biography Andrew Jackson: His Life and Times, “The republic survived. The Union was saved.”

The Union may have been saved, but the struggles for the citizens would continue. The war made the US economy weak, and the nation was in debt. Rising tensions with Native Americans were causing issues in the South and West. New innovations like the cotton gin and steamboat increased the souths relience on slavery and rivived power for the slaveholders. The Federalists of the North were fed up with the Virginian Aristocrasy who had claimed the executive 7 out of 8 terms so far.

Enter James Monroe

James Monroe entered office in 1817, the 4th Virginian to hold the Presidency. Monroe understood the divide that was growing in the expanding union. He selected his cabinet to unite the Republican party and Union after the war of 1812. The intent, in his words, was to “Exterminate all party divisions in our country, and give new strength and stability to our Government.” He selected a geographically balanced cabinet: Secretary of the Treasury William H. Crawford of Georgia, Secretary of War John C. Calhoun of South Carolina, Attorney General William Wirt of Virginia, and Postmaster General Return J. Meigs Jr. of Ohio. And for the coveted position of Secretary of State, he selected former Federalist John Quincy Adams of Massachusetts.

During Monroe’s term, the country’s passions were tempered by his steady leadership, but the divide continued to grow. Issues over slavery were on the rise, only cooled for a moment with the Missouri Compromise. The Tariff of 1816, one of the first protective tariffs in the country’s history, passed during the Madison administration, was starting to irritate the agricultural south as it overwhelmingly benefited the industrial north.

Monroe’s chosen successor was Adams, but some republicans didn’t think he could defeat William H. Crawford, the former Secretary of the Treasury. Crawford was seen as a dangerous man who wielded power selfishly and punished foes. So, a block of republicans began to court Jackson into the race. Jackson was no fan of Crawfords, but he also didn’t want to be President. However, in 1822, when a group of Tennesse lawmakers nominated him, he couldn’t refuse the call to service. This divided power in the party.

The divided power led to an election where none of the candidates secured a majority in the electoral college. The top finishers were: John Quincy Adams, Andrew Jackson, William H. Crawford, and Henry Clay. The election was sent to the House of Representatives to decide, and Henry Clay threw his support behind John Quincy Adams, making him the 6th President of the United States. In return, Clay was appointed as Secretary of State. This enraged Jackson, who finished with more votes in the electoral college and with a higher percentage of the popular vote. Jackson and his followers dubbed the election the Corrupt Bargain.

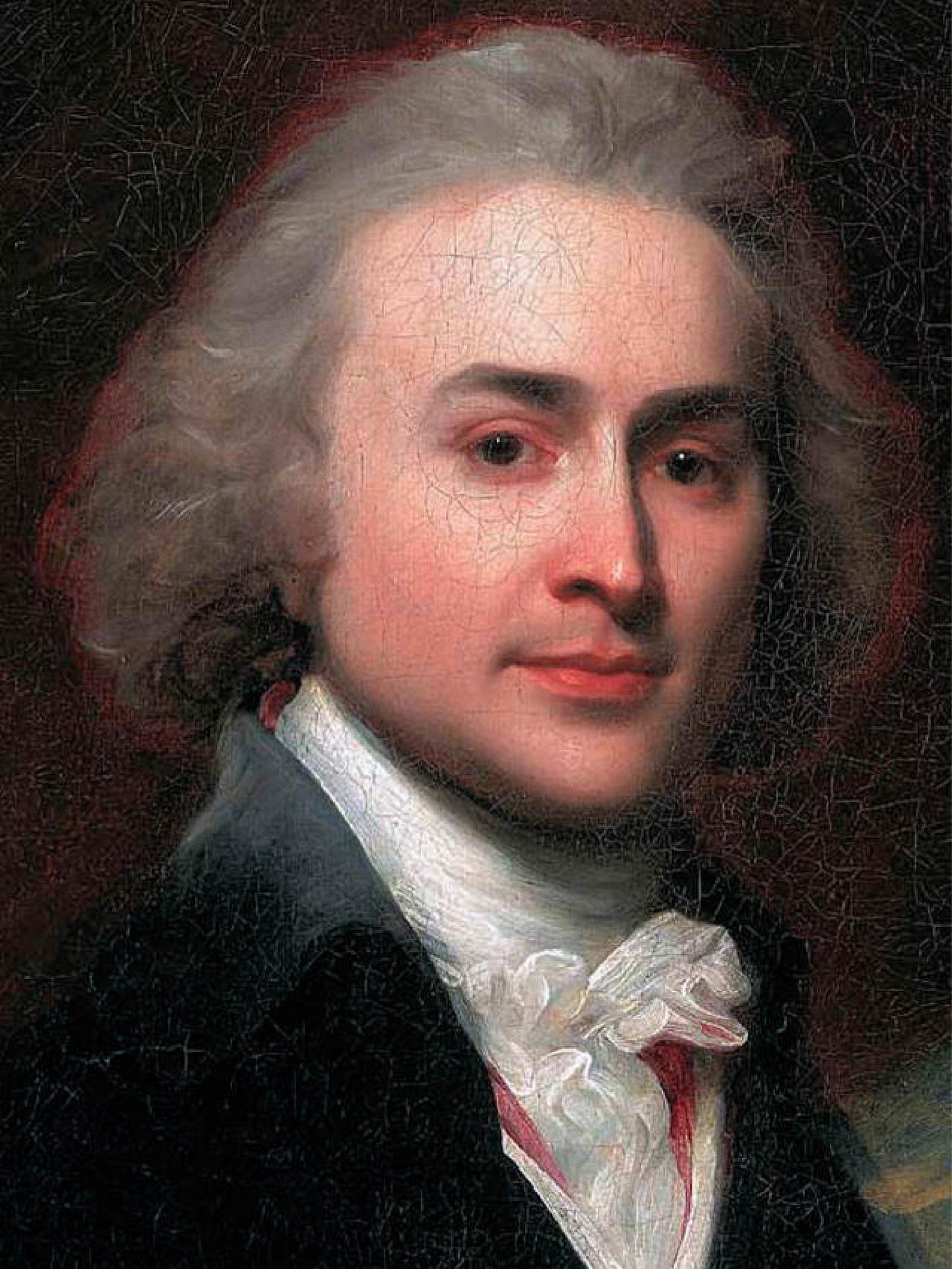

Enter John Quincy Adams

John Quincy walked into an untenable position as President. The Corrupt Bargain painted him as the last remnants of a decaying aristocracy, propped up by a junto of self-proclaimed virtuous republican power. John Quincy was a man who meant well, a man of principle, filled with a wealth of diplomatic and governing experience. President after President trusted him to read foreign adversaries and negotiate on the Union’s behalf. His communications were vital in the young nation developing long-lasting freedom. He struggled to manage a growing divide between the north and south as president. His decisions were that of a leader who was out of touch with a large portion of the nation. This wasn’t intentional, but rather circumstantial. The thing that made John Quincy a brilliant statesman was his experience, but it was also his weakness. He spent approximately 24 years overseas prior to becoming president, which isolated him from the American citizenry as much as it did politically.

In 1828, Andrew Jackson capitalized on Adams's failures and harnessed a new democratic power to defeat the republican aristocracy that had lost its way.

The Republican power that built our union and governed her to prosperity and expansion also nearly wrecked her in the ditch with embargos, tariffs, and war. As the years wore on, virtuous leadership became harder and harder to find, which divided the power inside the party. The backdoor maneuvering looked suspicious to those outside the power circle. This, combined with the country’s economic woes and growing cultural divide, led to power sifting from the republican side of our democratic republic to the democratic side.

It was the threads of our old republican power that led to the new democratic power. Once finally woven together, stress had pulled them apart. In history, revolutions are frequent and easy, a self-governing republic is rare and difficult. Revolutions are born of dissent and passion—governing is successful when passions are tempered and dissent is turned into debate. When we visit the Jacksonian Era, we will learn if the people had any better luck leading than the aristocracy.

If you’re enjoying this series on the Power, Party, and People that shaped our nation, consider coming to a Madisonian Republican event. The next opportunity is February 18th, 4 pm - 6 pm. You can RSVP at madisonianrepublicans.com.