A Time to Build

A populist reform movement

A few weekends ago, my wife and I traveled to Washington, DC, for a brief respite from our many responsibilities and children. We, of course, stayed at the Madison Hotel and visited Ford Therate and the Capitol building. Our first stop in DC was to Politics and Prose to pick up some new books. I chatted with our Uber driver on the way from the bookstore to the Capitol building. He was originally from Gauna. He traveled to the US on a visa and was granted amnesty during the Reagan administration in the late 80s. He told me, “People from all over the world want to come to America for the opportunity.” As we chatted, it was obvious that the immigrant Uber driver from Gauna understood the values and principles better than many natural-born citizens. He was thankful for the safety and opportunity the institution of the US government had provided to him over his lifetime and said regardless of its many faults, it was still “the best place to live.”

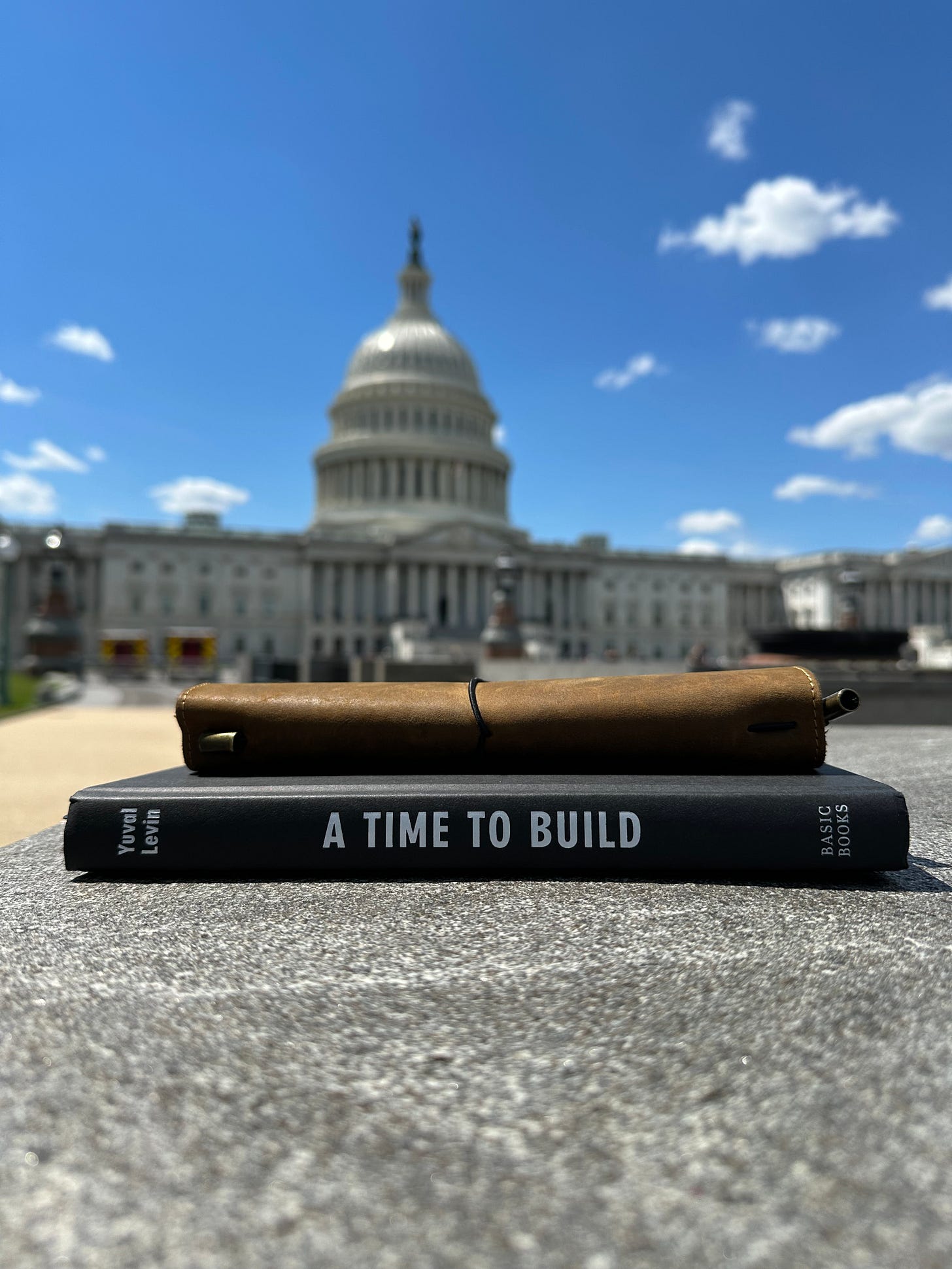

Saturday’s weather was gorgeous. The temperature was in the low 70s. The hot sun was cooled by a gentle breeze which sent the seasoned trees around the Capitol swaying in the foreground of the crystal blue sky. Vanessa and I decided to sit near a tree planted in front of the Capitol and read. I opened up A Time to Build by Yuval Levin and dug in.

Levin does a great job identifying many social and political issues our society currently faces. He discusses the rise of populism, the distrust of current institutions, and the concentration of power. In chapter two, he discusses how we don’t consider our institutions formative but performative.

When we don’t think of our institutions as formative but as performative— when the presidency and Congress are just stages for political performance art, when a university becomes a venue for vain virtue signaling, when journalism is indistinguishable from activism—they become harder and harder to trust. They aren’t really asking for our confidence, just our attention.

The performative institutions and the lack of trust in them have led to a rise in political “outsiders.” What is an “insider,” and what is an “outsider?” An insider is someone who either works inside the institution or supports the institution. The institution of campaigning is supported by fundraising and donations. So, someone who has never run for public office may present as an “outsider.” Still, if they spent years in the private sector donating and fundraising money for political candidates, they are as much part of the swamp as anyone else. Since institutions focus on our attention rather than confidence, it becomes harder for the average citizen to distinguish between genuine and not.

During times of distrust of institutions, people search for leadership, and an outsider typically leads the populist movement. People like Andrew Jackson, Teddy Roosevelt, Bernie Sanders, and Donald Trump. Or are these people insiders? Jackson was a major general in the Army and a Senator before becoming the first American populist president. Roosevelt was from a wealthy and powerful family. Bernie has been a representative of the government since 1991. Trump has spent years donating and building relationships with powerful politicians like Rudy Giuliani and the Clintons. Each of them may not have been of the people, but they speak for the people by speaking against the institutions. In order for people to have a successful populist movement, they need a leader who is genuine, who listens to the people and guides them to reform rather than revolution.

In chapter three, he dives into the push for congressional transparency that gained steam in the 1970s, pointing out how many of the proposals for reform often miss the mark. I think it’s important to zoom out for a moment and try to understand why this happens. Transparency becomes an issue when authority fails to communicate with those they lead. Communicating complex information becomes difficult when the groups are too large. Keeping the groups small was a feature of our Republican system until 1911, that’s when our house was capped at 435 members. At the time, the population was around 100 million. By the 1970s, it was 200 million. The representative-to-citizen ratio at the time was 1:220,000. By the 1970s, the representative-to-citizen ratio was around 1:456,000. The larger districts created difficulty for the representatives to communicate with those they represent.

I recently spoke with a staffer who works on capitol hill. They told me they have a staff of 18 attempting to communicate with almost 800,000. Saying with exhaustion, it’s nearly “impossible.”

The failed communication by the institution of Congress and the rise in new technologies led to the concentration of power in the media. Levin writes.

There are certainly some significant concentration of power in some facets of the media, as there are throughout our economy. It’s true that a few large corporations control the means by which vast swaths of our society obtain their information. But the most significant of these are not actually media companies, in the sense that they don’t produce journalistic content; they are information management and social media companies, such as Google, Facebook, and Twitter. They possess the ability to filter our information through complex algorithms that can exercise enormous influence over what reaches us and under what circumstances.

The combination of performative institutions and concentration of media power has led to journalist behaving in a way that is more attention-seeking rather than informative. Levin writes.

Too often now, prominent political reporters in particular can be found engaged in a never-ending, loose, unstructured form of conversation carried on television, on Twitter and elsewhere—a conversation carried on in public view but outside of the procedural and ethical boundaries of their workplaces, which makes it increasingly difficult for journalism to lay claim to institutional integrity and nearly impossible to avoid petty partisanship.

Instead of these members debating their ideas in private and shaping thoughtful answers crafted to inform the public, the debate is done live, with each party saying the first thought that pops into their mind to get attention.

The rise of social media forced traditional media to compete in the marketplace of outrage to maintain profitability. Shifting the focus to entertainment and profitability instead of information and professionalism.

Another institution Yuval writes about is the family. The family is the first institution we are all acquainted with, it’s where we learn to communicate, compromise, and debate. It’s where we learn our boundaries as individuals and how to respect others.

The family is our first and most important institution, not only from the perspective of humanity, but also (and more simply) in the life of every individual. It’s where we enter the world, literally where we alight when we depart the womb. It gives us our first impression of the world, and our first understanding of what it is all about. It then sees us through some of our most vulnerable years of life, taking us by the hand as we progress from formless ignorance of the newborn through the formative innocence of early childhood to the fearful insecurities of juvenile transformations and hopefully, eventually, to a formed and mature adjusted posture in society. This is a process of socialization, and therefore fundamentally of formation. But it is not a formation that happens through instruction so much as through example and habituation. The family forms us by imprinting its forms upon us and giving us models to emulate and patterns to adopt.

The family does all this by giving each of it’s members a role, a set of relations to others, a body of responsibilities, and a network of privileges. Each of these, in its own way, is given more than earned and is obligatory more than chosen. Although the core of human relationships at the heart of most families—the marital relationship—is one we enter into by choice, once we entered it that relationship constrains the choices we make. The other core familial bond— the parent-child relationship— often is not optional to begin with, and surely must not be treated as optional after that. It imposes heavy obligations on everyone involved, and yet it plays a crucial role in forming us to be capable of freedom and choice.

The family structure teaches us how to serve and be free. It allows us the opportunity to learn through observation and instruction. It forms us into an individual and a citizen. It does this by dividing the responsibility of survival among its members by giving them roles. Ellie, my daughter, who is six, watches the dog while we are outside. She won’t let him play in the mud because, in her words, “I don’t like cleaning off his paws. If he wants to play in the mud, he needs to learn how to do it himself.” Moments later, she and her twin Saide are playing in the mud together. I tell them to get out. I said, “If you want to play in the mud, you need to learn how to clean yourself off. That includes your body, shoes, and clothes. Until then, not today.” Sure, there are days when I let them play in the mud. They are kids, and those experiences are important. But I am in charge of when that happens, but I want them to be in charge of it. I want them to bathe themselves, wash their clothes, and clean their shoes. And I want them to be in control of their own happiness. I want them to have more freedom. The family structure teaches us to have freedom by serving others inside the family. It teaches the ambition of freedom through the ambition of self-reliance. The more successful the family structure, the more freedom each of the members has. The same goes for the institution of our republican government. The power is divided into different roles, the Executive, the Senate, the House, and the Judiciary. The more successful the government is at teaching, shaping, or forming self-reliance than dependence among its people, the more freedom the people will have.

Much like the child is dependent on the parent for their freedom. So too, is the citizen dependent on successful institutions for theirs. Levin writes.

Functional institutions are most important for people who don’t have power or privilege. And though our institutions can become cold and bureaucratic, they are essential to our acting on our warmest sentiments; without them we grow isolated, alienated and disillusioned.

Family institutions fail when communication fails between parents and children, parents fail to teach, and the children are left dependent. The children may rebel against the institution and want to run away from home, but they will find what they really want is not to abandon the institution but a stronger institution. One that both listens and guides, providing proper authority and structure for the child to grow independent and one day become the authority if they choose— to have freedom. Our institutions and we as Citizens are much like a parent-child relationship in this way. The institutions are talking at and over each other, and we, the citizens, are left unheard with no leadership. We act as if they want to tear the institutions down, but what we really want is stronger ones with leaders who listen and guide.

Most institutions— and not just at the familial, communal, or local level— are in effect small ponds in which individual members can be big fish. We can be known and appreciated, we can be missed when we are absent, we can take part in the sort of interpersonal politics that we like to complain about but actually enjoy and need: office politics, club politics, church politics, school politics. Each institution provides a place where everybody knows your name, your quirks, and your strengths and weaknesses. The absence of such place in the lives of many Americans has a lot to do with the breakdown we see in parts of our national life. As some of our small ponds have disappeared or been drained out, the opportunities we have to be big fish have grown more scarce.

Our institutions may have a lot of faults, but they still make up a country that is “the best place to live.” And although they appear to be failing, they are not failed and, therefore, can be repaired. The first step we could take would be to elect leaders who understand the actual failing of our institutions. Communication. These leaders would focus on creating more effective communication with those they lead. Federal government representatives should focus their time on uncapping the house to help alleviate the responsibilities of government and help communicate with those they lead. A representative of state governments should focus on campaign finance and the electioneering process. Ensuring it is more a form of conversation and information rather than entertainment and fundraising. To ensure voting is safe, secure, and readily available to the citizenry.

Social media companies like Twitter could restructure their algorithms to be funneled by zip code or congressional district, ensuring that when a person walks into the town square and speaks, they speak to their town, not a hand-picked selection of people who believe the same thing. It’s great that we can find people like us, but we should communicate more with those in our communities.

For more on this, check out my latest Thank You For Sharing episode, discussing the social aspect. The Internet dating scene.

Another populist leader in our nation’s history was Abraham Lincoln. He, like the others, spent years inside the institution before becoming the beloved leader of the Union. Lincoln debated seven times during his campaign with Stephan Douglas for the Senate seat in Illinois. This experience brought Lincoln close to the people, he understood what they wanted. This is why he was a confident leader of a factious country and cabinet. He also led during a time when many institutions were struggling. For decades, the country had been led by accidental leaders (John Tyler), party-picked men (James Polk), and compromise candidates (Franklin Pierce and James Buchanan). Lincoln was the first leader the people voted for rather than against in decades. Lincoln didn’t just speak for the people by speaking against the institutions (the Democratic Party and the slaveholders); he listened to the people and built a new institution, the Republican Party.

Sunday in DC was gorgeous again. We walked the mile and a half from the hotel to Ford’s Theatre for our tour at 10 am. It started in the museum, where were saw quilts signed by multiple presidents and stories of the men who helped repair our fractured union. Then we went upstairs and sat for the performance. A park ranger performed the story of the coup attempt by radical Democrats and the assassination of Lincoln. The story was gripping and delivered with Shakespearean eloquence. The performance had me in tears. Lincoln was the target of a different kind of populist. One led on the foundation of revolution and division rather than reform, debate, and compromise. They couldn’t win the war of ideas, or the war on the battlefield, so they tried to tear down the institution by targeting President Lincoln, Vice President Andrew Johnson, General Ulysses S. Grant, and Secretary of State William H. Seward.

After my weekend away reading and listening to history, I walked away more confident than ever that we would find the right leaders to lead a populist reform movement rather than a populist revolution. Leaders who listen and guide rather than seek our attention and divide. Leaders who build rather than tear down. Leaders who debate rather than speak at us. We just need to create an institution where good leadership can survive and thrive.